Long Wait for Justice as Court Sets 2026 Trial in EFCC's Gombe Fraud Case.

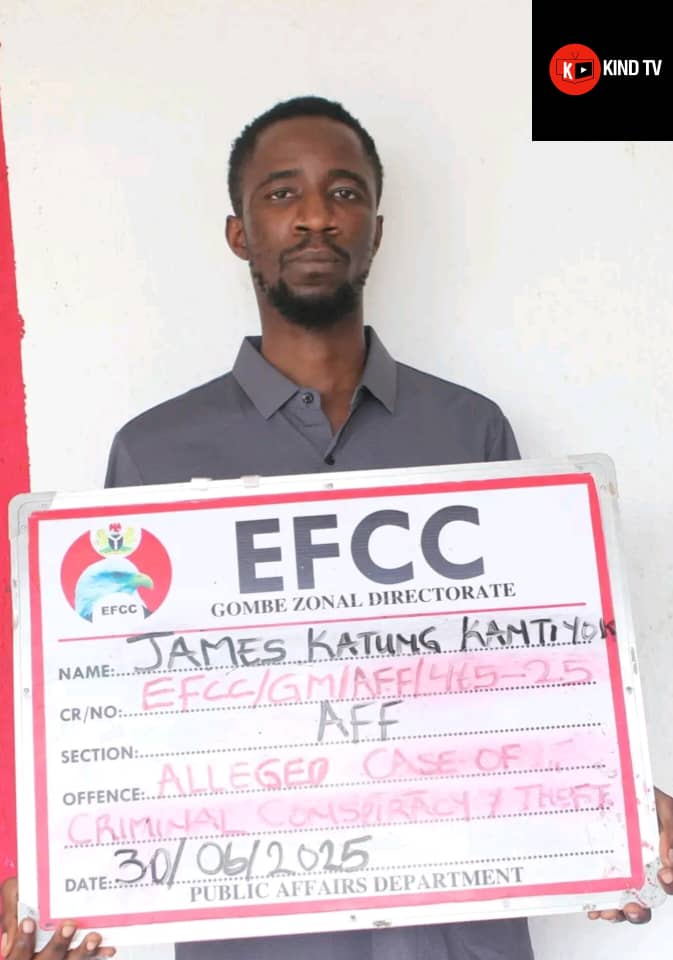

— The slow grind of justice once again played out in Gombe this week, as the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission arraigned a former bank staff member, James Katung Kantiyok, over allegations of diverting $105,000 and N2 million belonging to his employers. The courtroom atmosphere, still and heavy like an untended archive, carried the quiet tension often seen when financial crimes test the resolve of Nigeria’s justice system. Kantiyok, once entrusted with a bullion operation, now stands accused of siphoning funds over a period spanning April 2024 to June 2025. Prosecutors insist he knowingly retained what they describe as proceeds of criminal breach of trust. The charges, seven in all, fall squarely under the Money Laundering (Prevention and Prohibition) Act of 2022. Despite the seriousness of the allegations, the defendant entered a plea of not guilty. What followed brought the familiar ache of déjà vu for observers who have tracked Nigeria’s financial crime litigation over the years. The prosecution pushed for remand, emphasizing the gravity of the charges. Yet, after what seemed like a measured pause, the court granted bail, an eye-catching N70 million, along with a pair of hefty conditions. One surety must be a senior government officer. The other must be a reputable resident of Gombe. Kantiyok must surrender his passport and report to the EFCC monthly. The ruling itself was not unusual. Nigeria’s courts routinely favour bail in non-violent cases, even where the sums involved are staggering. But it is the timing and the wider implications that raise the eyebrows of analysts. Here lies the more troubling thread: the trial will not begin until March 3 and 4, 2026. That is almost a year away, an eternity in a system already weighed down by swirling allegations of judicial lethargy. For many legal watchers, this adjournment is not merely a scheduling gap. It is part of a deeper pattern in which high-profile financial crime cases drift, stagger and occasionally expire in procedural paralysis. The result is a public perception, sometimes whispered, sometimes declared, that the wheels of justice move at different speeds depending on who stands in the dock. The decision to fix trial dates so far ahead subtly reinforces this perception. For a case involving traceable financial transactions, documentary evidence and a defendant previously in a position of fiduciary responsibility, the pace appears unnecessarily glacial. The risk is predictable: the longer the case drags, the more it chips away at public confidence. The matter now waits for its 2026 opening, a reminder that Nigeria’s struggle with judicial efficiency is far from resolved. What happens next will signal whether this case becomes another lost ember in the system or a rare instance where delayed justice still finds its mark.

| 2025-11-21 20:30:45